A Casualty of War

A Long and Faithful Career

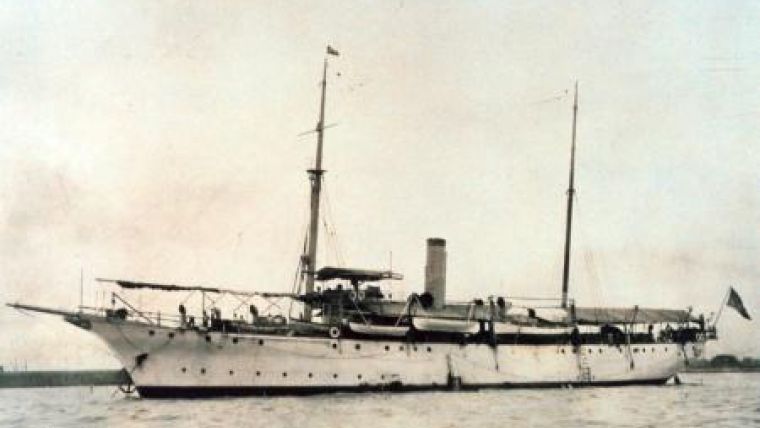

In 1899, a new ship was launched at the Crescent Shipyard in Elizabethport, New Jersey, USA. This vessel was a Coast and Geodetic Survey ship designed and constructed for rugged service in the far reaches of Alaska. Although 196 feet long, the ship appeared boxy, almost like a section had been cut out of its middle. Primarily a steam vessel, it was also brigantine rigged. When under sail, the ship carried 4,500 feet of canvas.

Its new civilian commander was Frank Wally Perkins and its name was Pathfinder. The complement consisted of civilian C&GS officers and a crew of 65 Navy enlisted personnel. This odd configuration of crew and officers occurred because the Navy had withdrawn all officers from C&GS duty the year before in response to needs arising because of the Spanish-American War. Navy officers were never to return, ending 2/3 of a century of naval officers serving on the larger ships of the Survey.

The little ship left Newport News, Virginia, on 16 June 1899, and began its transit to the Straits of Magellan. Among the interesting aspects of this transit was the coaling of the ship at Santa Lucia where the ship was coaled by a steady stream of women carrying 100-pound baskets of coal on their heads. In 2½ hours the women loaded 115 tons of coal in the bunkers of the Pathfinder. Then while passing through the Straits of Magellan, the ship encountered some of the last of the Patagonians who in spite of being at 50 degrees south in the first month of Southern Hemisphere winter, were indifferent to the cold. The adults wore few clothes while the children were completely naked. Fortunately the ship encountered none of the storied storms of this area and after entering the Pacific continued to the north, arriving in San Francisco on

17 September after a three-month passage. Because of the lateness of the season, the ship proceeded to Honolulu and conducted surveys in the Hawaiian Islands during the winter. Foreshadowing the future career of the ship, Perkins was detached from the ship in March 1901 and ordered to proceed to the Philippine Islands to conduct reconnaissance for establishing a Coast and Geodetic Survey base in the then new American territory. John J. Gilbert took over as commanding officer. In the late spring of 1900, the ship sailed for its intended working grounds in Alaska, its first Alaskan surveys in the vicinity of St. Michael and the entrances to the Yukon River. This was one of the greatest Alaska ports at the time, as gold-seekers headed to the Klondike via the Yukon River or the gold fields of Nome across Norton Sound were booking passage to St. Michael.

The following year the ship once again returned to Alaska and conducted surveys in the vicinity of Dutch Harbour and the eastern Aleutian Islands. However, the ship’s crew received a major surprise at the end of the season as the Pathfinder was ordered to Manila and left Dutch Harbor for the Philippine Islands on 17 October 1901. The ship arrived in Manila on 18 November 1901, and never left the islands again with the exception of shipyard visits to China and coaling visits to Sandakan, Borneo.

Over the next forty years the ship would ply the waters of the vast Philippine archipelago — 7,000 islands spread over an expanse of ocean covering approximately 500,000 square nautical miles. Two generations of Coast and Geodetic Survey officers would travel to Manila for assignment to either this ship or the Philippine insular government survey ships Research I, Romblon, Marinduque, and Fathomer. They would encounter over 700 dialects and cultures ranging from Spanish-influenced Catholics in the northern islands, Moro Muslims in the southern islands, and even primitive Philippine tribal groups just emerging from the Stone Age. Huge salt-water crocodiles, king cobras, tropical diseases, and a plethora of animals, insects, and types of vegetation that would bite, sting, and irritate in a variety of manners were the lot of the field surveyors attached to these ships. Often, the only warnings of an impending typhoon were those observed by the surveyors and, on at least two occasions, the Pathfinder was driven aground while shore crews were sometimes left to their own wits to survive these great storms on remote islands.

In spite of these hardships, the work progressed and by the late 1930s most of the triangulation, shoreline topography, hydrography, and tidal observations had been completed. At this time, a new ship was being built on the west coast of the United States that also would be named Pathfinder in honour of the career of the older ship. Thus, the venerable old ship was renamed Research, for the earlier C&GS vessel that had worked in the Philippine Islands. Concurrently, the C&GS was embarking upon a programme of training Philippine native islanders to take over the functions of the C&GS. Men such as Andres Hizon and Cayetano Palma, both future directors of the Philippine Coast and Geodetic Survey, were part of this programme as was Constancio Legaspi, a future assistant director. These men were incorporated into the C&GS as deck cadets and officers and trained to ultimately take over the running of the Philippine survey. This training programme was interrupted in December of 1941.

On the night of 24 December, Manila was bombed by Japanese aircraft. Commander George Cowie, director of the Philippine C&GS, was killed as he was trying to salvage equipment and survey data from the C&GS Engineer Island facility. The bombing set in motion a series of events that culminated in the loss of the Research within a matter of days. The commanding officer of the Research was reassigned as director of the Philippine C&GS operations while the executive officer, Lt. (j.g.) George Morris, became commanding officer. However, over the next few days, Ensign Constancio Legaspi, was the officer of the deck and George Hutchison, a long-time employee of the C&GS and insular government, became acting chief engineer.

On the morning of 28 December, the ship received orders to report to Corregidor. Before the ship could get underway, a wave of Japanese aircraft came over and bombs rained around the Research and other ships in the harbour. Legaspi was the only officer on board at the time as Morris had gone ashore to arrange for provisions and other matters. Although the Research did not suffer a direct hit, Legaspi reported that, “The portside plating just above the water line was badly shattered and the after deck was on fire. All the boats including those on the water were burned except the whaleboat and the motor whaleboat which we saved from the fire. I immediately ordered the men to put out the fire using buckets and hand pumps while the engineers on watch were raising the steam to operate the steam pumps. The fire was put out after about two hours fighting. However, the cabin, after railings, awnings, wardroom, and part of the after deck were burned.” The ship survived this initial onslaught as its machinery was still operating and it proceeded to move to Corregidor that evening with Morris, Legaspi, Hutchison, and a few other crew. Morris left the ship the following morning to discuss plans with Andres Hizon who was on the Fathomer. During his absence the ship came under attack again during the first of 614 Japanese bombing raids on Corregidor over the ensuing months. The ship appeared to suffer no serious damage during this attack. That evening Morris left the ship and took an Army transport to Manila to acquire supplies for the ship. However, the next day, 30 December, bombs once again fell close aboard while Hutchison, Legaspi, and crew members huddled below deck for protection. Ultimately, they took the remaining ship’s boats and sought protection ashore. Legaspi and Hutchison returned to the ship about 4.30pm and discovered that it had sprung a leak and the boiler and propulsion machinery were under water. Hutchison also counted sixty-two holes in the ship inflicted by shrapnel. Hutchison went back ashore and obtained permission to beach the Research on the northeast side of the island. A small tug was obtained whose captain brought the ship around the island and pulled it into shallow water. Hutchison expressed concern that the ship would not hold but this was disregarded. It was later seen that evening drifting to sea. Once again the tug was obtained to pursue the ship, but as it was drifting to the north through minefields placed in the channel between Corregidor and the Bataan Peninsula, the chase was given up. The tough little ship that was meant for Alaska service, but instead had survived decades of typhoons, uncharted reefs, and other tropical ocean dangers, was drifting towards the Bataan Peninsula where it ultimately grounded near Alasasin Point. Here according to Hutchison, virtually everything of value was stripped during the war. Whether any remnants of its hulk remain is unknown. In Hutchison’s words, “So ended the long and faithful career of the good old ship Pathfinder.” Concerning Constancio Legaspi, Hutchison reported, “Cadet Legaspi was of vast assistance to me and conducted himself in a very seamanship manner and showed no signs of fear.” Legaspi in his turn, reported “During all those critical days aboard the ship and at Engineer Island when the ship was set afire, the men all stood by me. I recommend that they be commended for their courage and attention to duty during the period of the crisis. There was no casualty and only a few suffered minor injuries.” Lt. (j.g.) Morris stayed with American forces on Corregidor and was wounded and captured during its final fall in May of 1942. He was incarcerated for over three years as a prisoner-of-war and survived the infamous Japanese prison hell ship Enoura Maru on its voyage from the Philippines to Japan. A fellow C&GS officer, Joseph Stirni, died on this ship when it was bombed by American forces in Takao Harbour, Formosa (Kaohsiung, Taiwan).

As a footnote, less than two weeks after the loss of the Research, the new ship Pathfinder was launched on 11 January 1942. This ship was a worthy namesake of the ‘old Pathfinder’ and it was said of this ship “that the road to Tokyo was paved with Pathfinder charts.”

Value staying current with hydrography?

Stay on the map with our expertly curated newsletters.

We provide educational insights, industry updates, and inspiring stories from the world of hydrography to help you learn, grow, and navigate your field with confidence. Don't miss out - subscribe today and ensure you're always informed, educated, and inspired by the latest in hydrographic technology and research.

Choose your newsletter(s)