Fate of Titanic Linked to Lunar Event

The sinking of the ocean liner Titanic in the night of 14 April 1912 is perhaps the most famous – and most studied – disaster of the 20th century. Astronomers from Texas State University-San Marcos, USA, have applied their celestial sleuthing skills to the disaster to examine how a rare lunar event stacked the deck against the Titanic. Their results shed new light on the hazardous sea ice conditions the ship boldly steamed into on that fateful night.

Inspired by the visionary work of the late oceanographer Fergus J. Wood of San Diego, who suggested that an unusually close approach by the moon on 4 January 1912 may have caused abnormally high tides, the Texas State research team investigated how pronounced this effect may have been.

What they found was that a once-in-many-lifetimes event occurred. The moon and sun had lined up in such a way that their gravitational pulls enhanced each other, an effect well-known as a 'spring tide'. The moon’s perigee — closest approach to Earth — proved to be its closest in 1,400 years, and came within six minutes of a full moon. On top of that, the Earth’s perihelion — closest approach to the sun — happened the day before, which was also the closest approach in 1,400 years.

Breaking from Greenland

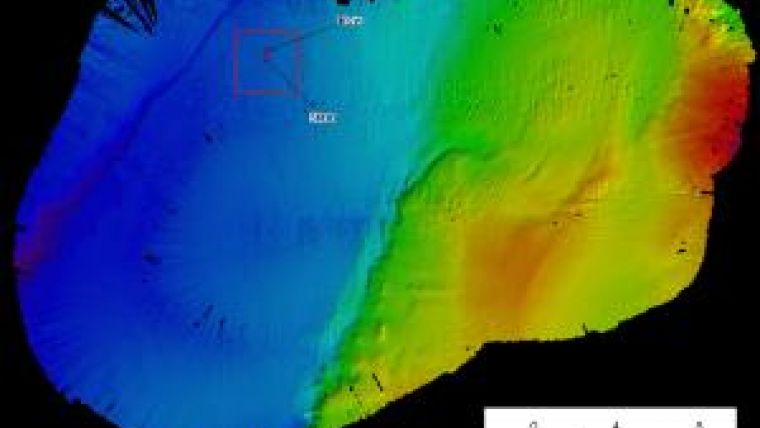

Initially, the researchers looked to see if the enhanced tides caused increased glacial calving in Greenland, where most icebergs in that part of the Atlantic originated. They quickly realised that to reach the shipping lanes by April when the Titanic sank, any icebergs breaking off the Greenland glaciers in January 1912 would have to move unusually fast and against prevailing currents.

Freed by spring tide

According to the Texas State group, the answer lies in grounded and stranded icebergs. As Greenland icebergs travel southward, many become stuck in the shallow waters off the coasts of Labrador and Newfoundland. Normally, icebergs remain in place and cannot resume moving southward until they’ve melted enough to refloat or a high enough tide frees them. A single iceberg can become stuck multiple times on its journey southward, a process that can take several years.

But the unusually high tide in January 1912 would have been enough to dislodge many of those icebergs and move them back into the southbound ocean currents, where they would have just enough time to reach the shipping lanes for that fateful encounter with the Titanic.

Texas State physics faculty members Donald Olson and Russell Doescher, along with Roger Sinnott, senior contributing editor at Sky & Telescope magazine, have published their findings in the April 2012 edition of Sky & Telescope.