SEAMAP 2030: unveiling Portugal’s seabed secrets

Portugal’s SEAMAP 2030 programme is on an unprecedented mission to meticulously chart the country’s maritime depths, contributing a vital piece of the global puzzle to the monumental GEBCO bathymetric grid. Guided by the Hydrographic Institute of Portugal (IHPT), this ambitious undertaking seeks to uncover the secrets of Portugal’s oceanic realm by 2030 by mapping the seabed with advanced technology.

If there were a metaphor for building the GEBCO bathymetric grid, surely a jigsaw puzzle would be most appropriate. “You have these little individual pieces that you put together to build the puzzle,” says Dr Vicki Ferrini, senior research scientist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and head of The Nippon Foundation–GEBCO Seabed 2030 Project’s Atlantic and Indian Oceans Regional Center.

There is, however, a big difference. When you buy a jigsaw puzzle, you have all of the pieces at hand. For the GEBCO grid, not all the pieces have been created yet. Fortunately, efforts are underway to build those pieces. When nations commit to mapping the seabed in their waters, they aren’t just creating individual pieces but larger, preassembled sections. “It accelerates what we’re trying to do at the global scale,” says Ferrini. Portugal is among the countries engaged in crafting a preassembled section.

Putting Portugal on the (seabed) map with the SEAMAP 2030 programme

Led by Portugal’s Hydrographic Institute of Portugal (IHPT), the SEAMAP 2030 programme has set out to map all the seabed within Portugal’s maritime space by 2030, using multibeam echosounders.

“In the beginning, we started collecting data for the proposal for the extension of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles,” says Rear-Admiral João Paulo Ramalho Marreiros, director general of the IHPT. If granted under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the extension of the continental shelf would see Portugal gain sovereign rights over the proposed area, which is the size of Europe, for exploitation of the seabed.

In January 2004, Marreiros was the commander of the Portuguese Navy vessel NRP D. Carlos I, one of the two hydrographic vessels fitted with multibeam echosounders to map the seabed. It was the official start of this survey campaign. To gather the data for the proposal, “we sailed about 200 to 300 days a year for about six years,” says Marreiros. After capturing the data needed for the proposal, “we continued doing the surveys to complement the data for some specific areas where more detail was required”. The IHPT collects and processes almost all of the seabed data, with a small proportion coming from scientific cruises and companies operating within Portugal’s maritime areas and who are willing to share their data.

Approximately 56% of the seabed in Portugal’s maritime areas, including the exclusive economic zone and the proposed extension of the continental shelf, has now been mapped with multibeam echosounders. To reach their goal of completely mapping this area by 2030, “we need to spend 100 to 150 days surveying, every year until 2030,” Marreiros says.

Deep challenges to be resolved

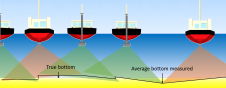

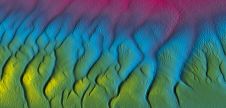

The advent of multibeam echosounders brought the potential to map the seabed in unprecedented resolution. Just how fine or coarse the resolution is depends on the distance between the multibeam transducer to the seabed. The shorter the distance, the higher the resolution that can be achieved. Almost all seabed mapping is done from vessels. When those boats pass over deeper waters – over a trough or off the continental shelf, for example, the resolution will become coarser than when that boat is in shallow water. This is why Seabed 2030 has different target resolutions for different depth ranges. The SEAMAP 2030 program also has resolution targets that vary by depth.

Although IHPT SEAMAP 2030’s targets are finer scale than Seabed 2030’s targets, Marreiros would like to map deeper waters at an even higher resolution, particularly in areas of special interest. To do that, you need to bring the multibeam closer to the seabed, “and for that, we need autonomous vehicles that go near the ocean bottom.” Using autonomous vehicles to map the seabed is the next challenge of SEAMAP 2030, to be explored in the near future. Speaking about seabed mapping in general, Marreiros says, “To go from ships to underwater vehicles, we must invest in the development of reliable underwater autonomous vehicles.”

Alongside seabed mapping, Marreiros sees an increasing need for a “more detailed physical, chemical, and biological survey” in areas of special interest, such as hydrothermal sources near the Azores Islands discovered by SEAMAP 2030. “If you don’t know what is in the ocean bottom, how can we explore in a reliable and sustainable way?” he says.

Sharing to reach a common goal

Collecting multibeam data is only part of the work involved in seabed mapping. Afterwards, there is the need for data processing, quality control, and making the results accessible and usable. Alongside a higher resolution product, the IHPT prepares the data in grid format compliant with GEBCO.

“We [the IHPT] exist to serve the maritime community – everyone that uses the sea,” says Marreiros. “The principle is to collect data once and use it many times, it will enhance a safe and sustainable use of the sea,” he adds. The data collected will support research, sustainable use of the ocean and conservation efforts and navigation safety, “from which all may benefit,” Marreiros says.

“The SEAMAP 2030 is a wonderful initiative,” says Ferrini. “Part of the joy of the Seabed 2030 project is getting to meet and work with and build relationships with folks around the world. It’s been a pleasure to do that with colleagues in Portugal and to see this great product they’ve put out there for the world as they’ve become part of our global movement.”

For those countries who may not yet be fully committed to mapping the seabed in their respective exclusive economic zones, Marreiros encourages them to start moving forward now and share their data with an appropriate grid scale. “If we don’t know what is in the sea, we cannot make good decisions [about ocean uses]. It takes a lot of time, and effort to map the seabed. Nobody can do it in one or two years,” he says. “It might be expensive and demanding in the short term, but the benefits will clearly emerge in the future.”