Protecting offshore energy platforms

Securing pipelines and wind farms with the potential of USVs

As the world’s reliance on offshore energy sources grows, the use of unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) emerges as a promising solution for safeguarding vulnerable offshore platforms. This article explores the increasing demand for offshore energy, the susceptibility of these platforms to attacks, and the limitations of current inspection methods. By leveraging USVs, both military and civilian sectors can enhance security measures.

As the informed readership of Hydro International knows, in spite of advances in technologies such as big data and artificial intelligence – with some calling big data ‘the new oil’ – the world’s economy will depend on energy for the foreseeable future. This energy comes in two primary types: ‘legacy’ sources such as oil and gas, and ‘green’ energy sources such as solar and wind. Increasingly, nations and energy companies are searching for and extracting these legacy energy sources offshore, as well as undertaking new projects to harvest offshore wind energy. However, regardless of the type of energy being extracted or generated, these offshore platforms – especially oil rigs, oil and gas pipelines and wind farms – are incredibly vulnerable to attack.

The sabotage in September 2022 of Nord Stream gas pipelines that run from Russia to Europe under the Baltic Sea garnered international headlines. While most of the reporting focused on who had carried out the attack, what was lost in the search for a culprit was the vulnerability of these offshore energy sources to attack or other less insidious damage.

As the world becomes increasingly dependent on offshore energy sources, there has not yet been concurrent investment in resources to protect these multibillion dollar platforms. It is increasingly clear that current methods of inspecting offshore energy resources such as oil rigs and offshore wind farms are ineffective. Given the enormous strides in the use of unmanned maritime vehicles in the past few years and their ability to undertake a plethora of missions, the offshore energy industry needs to consider adopting these platforms to enhance security.

Legacy energy sources still in high demand

Investment in renewable energy sources has exploded in recent years, with governments providing incentives that have industry making huge bets on solar, wind and other green sources. That is good, and necessary as far as it goes, but all trend lines indicate that, for the foreseeable future, the world’s energy needs will continue to be met primarily by oil and natural gas. Offshore energy production of these legacy energy sources has increased over the past decade and now stands at over 2.5 million barrels of oil and almost three trillion cubic feet of gas a day.

For the United States, this massive production effort is sustained by hundreds of offshore drilling rigs, primarily in the Gulf of Mexico. The US government has made a major commitment to extracting even more energy from beneath the oceans and seas. As one example, the US Department of the Interior has opened up 25 regions in the US outer continental shelf to oil and gas exploration. However, environmental concerns – impelled by major events such as the Deepwater Horizon disaster in the Gulf of Mexico – have served as a brake on US offshore drilling.

While offshore oil and gas companies have been proactive in ensuring the safety of their offshore platforms, more needs to be done. Using current technology, this is dull, dirty and dangerous work that impedes comprehensive inspection of these production rigs. Platform operators depend on divers and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) to perform such inspections, but ROVs have a limited field of view and putting divers in the water involves substantial risk and increasingly high costs.

Offshore wind farms proliferating at a rapid rate

Offshore wind farms have seen explosive growth, and predictions of more wind farms in littoral waters point to exponential growth for this industry. Several offshore wind farms are in operation, and many more are planned. Offshore wind farms are garnering headlines across the globe for their sheer scale, and many nations are increasingly turning to them to decrease their dependency on energy from Russia, as well as to speed up their energy transition.

According to the World Economic Forum, the global capacity of large-scale wind farms is expected to increase ten-fold, from 34GW in 2020 to 330GW in 2030, and spread throughout 24 countries (up from nine today). Indeed, much of the reporting regarding offshore wind farms is focused on one nation besting the other in how it can field larger-and-larger wind farms faster than others.

To gauge the magnitude of this enthusiasm for offshore wind energy, the World Economic Forum report referenced above predicts that one trillion US dollars will be invested in these energy assets in the next decade. Sadly, there has been little dialogue on how to protect these expensive offshore wind farms, and they remain highly vulnerable.

Search for more effective means to protect offshore energy assets

As mentioned above, oil and gas companies recognize the need to protect their expensive offshore platforms, but the technology they are using to do so is decades old, expensive and inherently dangerous. And while there is little evidence that, given the newness of their industry, offshore wind farm owners are yet thinking about how to protect their expensive assets, if pressed to do so today they would likely adapt the methods currently in use by the oil and gas industry.

Juxtapose this dependence on legacy offshore energy protection systems with the rapid production and use of unmanned surface vehicles (USVs) today. These USVs are being fielded in both the military and civilian world and as these assets are put into the hands of operators, new and innovative ways are being generated to perform missions previously carried out by manned systems. One of the most prominent of these is to protect offshore energy sources.

While it might seem counterintuitive, much of the impetus to use USVs for these kinds of civilian missions emerged from their use in military exercises, experiments and demonstrations. Spurred by the need to have USVs perform some of the dull, dirty and dangerous work previously performed by naval vessels, the US Navy and Marine Corps have evaluated these platforms as candidates to perform a wide array of missions.

After observing these USVs capably performing these military missions over many years, civilian users began to evaluate their use for non-military missions such as port and harbour security, environmental sampling and monitoring, navigation applications, hydrographic surveys, water quality monitoring and mobile inspections of bridges, dams, oil platforms and pipelines. While all of these missions are important, it is the last one that is both urgent and the subject of this article.

A best practices example

While there are any number of capable and affordable USVs either currently in the field or in various stages of design or production, I will focus on one platform that is a commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS) system that has been in use for almost a decade and ‘wrung out’ in a wide variety of military and civilian events. This is not intended to be a ‘point solution’ to the challenge of protecting offshore oil rigs, oil and gas pipelines and wind farms, but rather an example of a more affordable and comprehensive means of protecting these crucial energy assets.

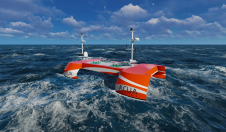

Maritime Tactical Systems (MARTAC), a Florida-based manufacturer of USVs, has fielded a family of low-cost, rugged and adaptable MANTAS T12 and Devil Ray T24 and T38 USVs. Part of the attraction of using these USVs to inspect offshore oil and gas platforms, pipelines and offshore wind farms is that they have seen extensive use in military exercises, experiments and demonstrations, as well as hundreds of hours of use in a number of civilian missions ranging from commercial canal and dam hydrography, to commercial power plant inspections, to port and harbour security.

This off-the-shelf technology can be used today to effect faster and more complete inspections of offshore wind farms and oil and gas platforms, along with their surrounding bottom-mounted pipelines, while dramatically decreasing the need for human divers. Three primary missions where those responsible for oil rigs, pipelines or offshore wind farms could utilize this USV technology include:

- For surface investigation, the Devil Ray, which is already equipped with a Furuno DRS4D-NXT Doppler radar and AIS, could also carry a SeaFLIR 280-HDEP multispectral surveillance system.

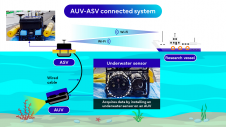

- For underwater imaging, the Devil Ray can be equipped with a Norbit iWBMS STX multibeam sonar, a forward-looking or sidescan sonar, or any of many other COTS underwater sensors.

- Since one of the early indicators of material failure of oil rig components involves oil and other material from the rig seeping into the surrounding water, the Devil Ray can be equipped with water monitoring sensors to include acoustic Doppler current profilers (ADCP), current-temperature depth (CTD) sensors, flourometers and other systems to detect changes in the water quality.

In each of the above missions, an offsite supervisory controller would have real-time camera, sonar and/or water quality visibility of the detections and observations being made by the USV. While there are many ways to employ these USVs to protect offshore energy sources, one initial use would be for an operator to have a Devil Ray on patrol on a predictable pattern inspecting the asset above and below water. If the USV discovers an anomaly and links the video back in real time, the operator will be alerted and can command the Devil Ray to linger in a particular area for more granular analysis using its integrated radar, camera and sonar sensor suite. If this investigation uncovers an area of concern, a diver can be deployed to make a repair.

Leveraging USVs to protect offshore energy sources

The same USV technology that is poised to assist the oil and gas and offshore wind farm industries is already being used to inspect critical infrastructure such as harbours, ports, inland waterways, dams, levees, canals, bridges and other infrastructure that cannot be safely or effectively inspected by humans. For example, a MANTAS T12 was used to conduct inspections of the Keokuk dam and energy centre, the Bagnell energy centre, the Elkhart hydro dam, the Central Arizona Project canal and other infrastructure.

The enormous investment that energy companies have made, and will continue to make, in offshore oil and gas rigs and offshore wind farms is one that these businesses must protect against failure, sabotage or other hazards. Current means of inspecting these assets are slow, costly and hazardous. Employing COTS USVs such as the Devil Ray can enhance the ability to safely and effectively deliver energy to the world.

Value staying current with hydrography?

Stay on the map with our expertly curated newsletters.

We provide educational insights, industry updates, and inspiring stories from the world of hydrography to help you learn, grow, and navigate your field with confidence. Don't miss out - subscribe today and ensure you're always informed, educated, and inspired by the latest in hydrographic technology and research.

Choose your newsletter(s)